Three Times Jacques Tati

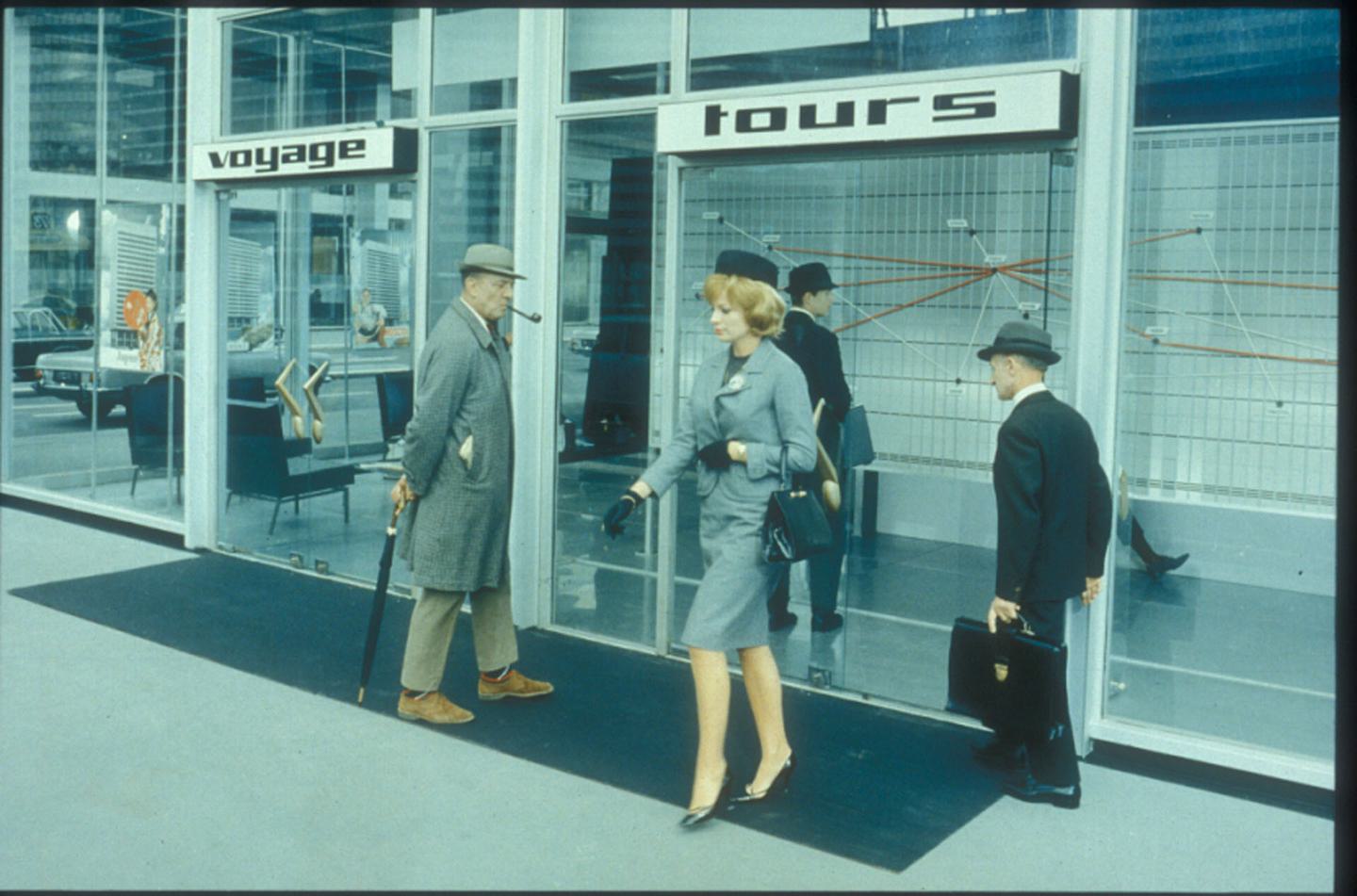

Jacques Tati, Mon Oncle, 1958

During 2011 Oslo Kunstforening would like to focus especially on dance, choreography and movement/motion in three different exhibitions.

Choreographers Malin Elgán (SE) and Emilia Adelöw (SE/NO) have each been invited to work on a solo presentation especially developed for our exhibition spaces. But first we would like to draw attention to one of film histories outstanding contributors to the development of post-war filmmaking; the French director Jacques Tati (1907-1982). Growing up during the silent movie era, working as a music hall mime artist during the second world war to then enter into film already tells us a lot about what he aimed at as a filmmaker. Equally influenced by silent films as the so-called “talkies”, and equally a product of pre-war and post-war France, his films balance between rural and modern times. He re-introduced the effects of the silent movies, experimented with sound in ways that no one had done before or after and managed to translated classic mime acts into a mix between everyday activities, choreography and performance. His films were never considered political or intellectual as La Nouvelle Vague (New Wave Cinema) from the same period, but they are much more than charming comedies. Today we see them as very precise time documents and in many ways Tati and his more politically oriented counterparts have more in common than we would think, although Tati choose to work with a different set of tools than his colleagues.

The aim of the exhibition is to point towards and develop the tradition of movement and dance being part of the contemporary art scene since the 1920s. Then artists such as Braque, Picasso, Matisse, Derain, Miró, de Chirico and Dalí were invited to collaborate with the Ballets Russes in Paris. The Swedish Ballet (Svenska baletten), also active in Paris during the same period worked together with artists such as Léger, Picabia, Foujita, de Chirico, Bonnard and Dardel. They were all aiming at assembling the avant-garde of art, music and dance to experiment and find new idioms for contemporary culture.

During the 1960s the exchange went in both directions. Artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg collaborated with dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, while Yvonne Rainer and Luncinda Childs entered the exhibition space with their dance performances and happenings. Rauschenberg worked as a dancer and choreographer for a couple of years at the Judson Dance Theatre were Rainer and Childs were part of the group together with Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay and Carolee Schneemann. They had all studied under musician and choreographer Robert Dunn, who has studied for John Cage and had worked with Cunningham since the 1950s. The Judson Dance Theatre opposed modern dance theory and practise and wanted to experiment and develop new ways to work with body, movement and dance performance.

What the post modern dancers and artist had in common with the filmmaker Jacques Tati was their interest in the everyday, investigating the primal elements of motion instead of the artificial, symbolic; it was about finding the magic in simple everyday activity. Instead of relating to art as “fine”, they wanted to act in the gap between art and life as Rauschenberg so eloquently put it. The fact that Jacques Tati choose to work with comedy does not mean that we should not study his contribution less seriously than his contemporaries within the fields of art, music and dance.

Jacques Tati (born Tatischeff) only made six feature films during his carrier. Between 1949 and 1974 he created Jour de fête (1949), Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953), Mon Oncle (1958), Play Time (1967), Trafic (1971) and Parade (1974). All the films document in one way or another France way towards modern times. They all focus on the materialistic development, something that is dealt with ambiguously and with comic overtones, and completely opposite to the intellectual ambitions of The New Wave Cinema.

Tati was known for working meticulously and very slowly. Many times the course of events in the films seem to be improvised, but absolutely nothing happens by chance. Tati aimed at and often succeeded in attaining artistic independence through all lines of production, meaning that no compromises were made for commercial reasons. His films should therefore be considered as productions of a sole creator, an auteur in the full sense of the word. From this perspective Tati was as much an artist as a filmmaker.

Oslo Kunstforening has chosen to show Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953), Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967), were Playtime is considered as the jewel of the crown. It took Tati nine years to complete the film. Tati build a huge set emulating a modern city, entitled Tativille (Tati city), on a patch of land he leased from the city in the outskirts of Paris. In the film Monsieur Hulot enters into an office building for a meeting but manages to go astray in the ultramodern office landscape. At the same time a group of American tourists arrive to the city for a 24 hours tour. During the day Monsieur Hulot and Barbara, a young American travelling with the tourist group repeatedly encounter one another until they end up spending the evening together at the restaurant Royal Garden. The film does not have a traditional plot, instead it focuses on the movements of the characters through the urban landscape and the sounds attached to a new futuristic lifestyle. The movie was shot with 70mm film, which offered higher quality than the more common 35mm, probably comparable to todays HD-format. The film won the acclaims of the critics; François Truffaut described Playtime as "a film that comes from another planet, where they make films differently”. Tati put in all his assets into the project counting on its expected success in Europe and the United States. But misfortunes such as a storm that tore down part of the set and other crises stretched the shooting schedule to three years. Tati was farced to take out large loans to cover the ever-increasing production costs. The film was a commercial failure and Tati ended up filing for bankruptcy. Time has caught up with his oeuvre, and Tati is now regarded as one of films greatest achievers. Today Playtime could very well have been a clean-cut art production that emphatically succeeds in capturing one of modern humanity's greatest dilemmas, our ability to constantly ignore our own nature.

Jacques Tati, Play Time, 1967

The aim of the exhibition is to point towards and develop the tradition of movement and dance being part of the contemporary art scene since the 1920s. Then artists such as Braque, Picasso, Matisse, Derain, Miró, de Chirico and Dalí were invited to collaborate with the Ballets Russes in Paris. The Swedish Ballet (Svenska baletten), also active in Paris during the same period worked together with artists such as Léger, Picabia, Foujita, de Chirico, Bonnard and Dardel. They were all aiming at assembling the avant-garde of art, music and dance to experiment and find new idioms for contemporary culture.

During the 1960s the exchange went in both directions. Artists such as Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg collaborated with dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham, while Yvonne Rainer and Luncinda Childs entered the exhibition space with their dance performances and happenings. Rauschenberg worked as a dancer and choreographer for a couple of years at the Judson Dance Theatre were Rainer and Childs were part of the group together with Steve Paxton, Trisha Brown, Deborah Hay and Carolee Schneemann. They had all studied under musician and choreographer Robert Dunn, who has studied for John Cage and had worked with Cunningham since the 1950s. The Judson Dance Theatre opposed modern dance theory and practise and wanted to experiment and develop new ways to work with body, movement and dance performance.

Jacques Tati, Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot, 1953

What the post modern dancers and artist had in common with the filmmaker Jacques Tati was their interest in the everyday, investigating the primal elements of motion instead of the artificial, symbolic; it was about finding the magic in simple everyday activity. Instead of relating to art as “fine”, they wanted to act in the gap between art and life as Rauschenberg so eloquently put it. The fact that Jacques Tati choose to work with comedy does not mean that we should not study his contribution less seriously than his contemporaries within the fields of art, music and dance.

Jacques Tati (born Tatischeff) only made six feature films during his carrier. Between 1949 and 1974 he created Jour de fête (1949), Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953), Mon Oncle (1958), Play Time (1967), Trafic (1971) and Parade (1974). All the films document in one way or another France way towards modern times. They all focus on the materialistic development, something that is dealt with ambiguously and with comic overtones, and completely opposite to the intellectual ambitions of The New Wave Cinema.

Tati was known for working meticulously and very slowly. Many times the course of events in the films seem to be improvised, but absolutely nothing happens by chance. Tati aimed at and often succeeded in attaining artistic independence through all lines of production, meaning that no compromises were made for commercial reasons. His films should therefore be considered as productions of a sole creator, an auteur in the full sense of the word. From this perspective Tati was as much an artist as a filmmaker.

Jacques Tati, Mon Oncle, 1958

Oslo Kunstforening has chosen to show Les Vacances de Monsieur Hulot (1953), Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967), were Playtime is considered as the jewel of the crown. It took Tati nine years to complete the film. Tati build a huge set emulating a modern city, entitled Tativille (Tati city), on a patch of land he leased from the city in the outskirts of Paris. In the film Monsieur Hulot enters into an office building for a meeting but manages to go astray in the ultramodern office landscape. At the same time a group of American tourists arrive to the city for a 24 hours tour. During the day Monsieur Hulot and Barbara, a young American travelling with the tourist group repeatedly encounter one another until they end up spending the evening together at the restaurant Royal Garden. The film does not have a traditional plot, instead it focuses on the movements of the characters through the urban landscape and the sounds attached to a new futuristic lifestyle. The movie was shot with 70mm film, which offered higher quality than the more common 35mm, probably comparable to todays HD-format. The film won the acclaims of the critics; François Truffaut described Playtime as "a film that comes from another planet, where they make films differently”. Tati put in all his assets into the project counting on its expected success in Europe and the United States. But misfortunes such as a storm that tore down part of the set and other crises stretched the shooting schedule to three years. Tati was farced to take out large loans to cover the ever-increasing production costs. The film was a commercial failure and Tati ended up filing for bankruptcy. Time has caught up with his oeuvre, and Tati is now regarded as one of films greatest achievers. Today Playtime could very well have been a clean-cut art production that emphatically succeeds in capturing one of modern humanity's greatest dilemmas, our ability to constantly ignore our own nature.

Jacques Tati, Play Time, 1967