Carl Michael von Hausswolff & Thomas Nordanstad

Carl Michael von Hausswolff & Thomas Nordanstad, Electra, Texas, 2008

Heaven

Everyone is trying to get to the bar

The name of the bar, the bar is called heaven

The band in heaven, they play my favorite song

Play it one more time, play it all night long

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens

There is a party, everyone is there

Everyone will leave at exactly the same time

When this party's over, it will start again

It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens

When this kiss is over it will start again

It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same

It's hard to imagine that nothing at all could be so exciting, could be this much fun

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens

Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens

– Lyrics, David Byrne/Jerry Harrison, Talking Heads, Fear of Music, 1979

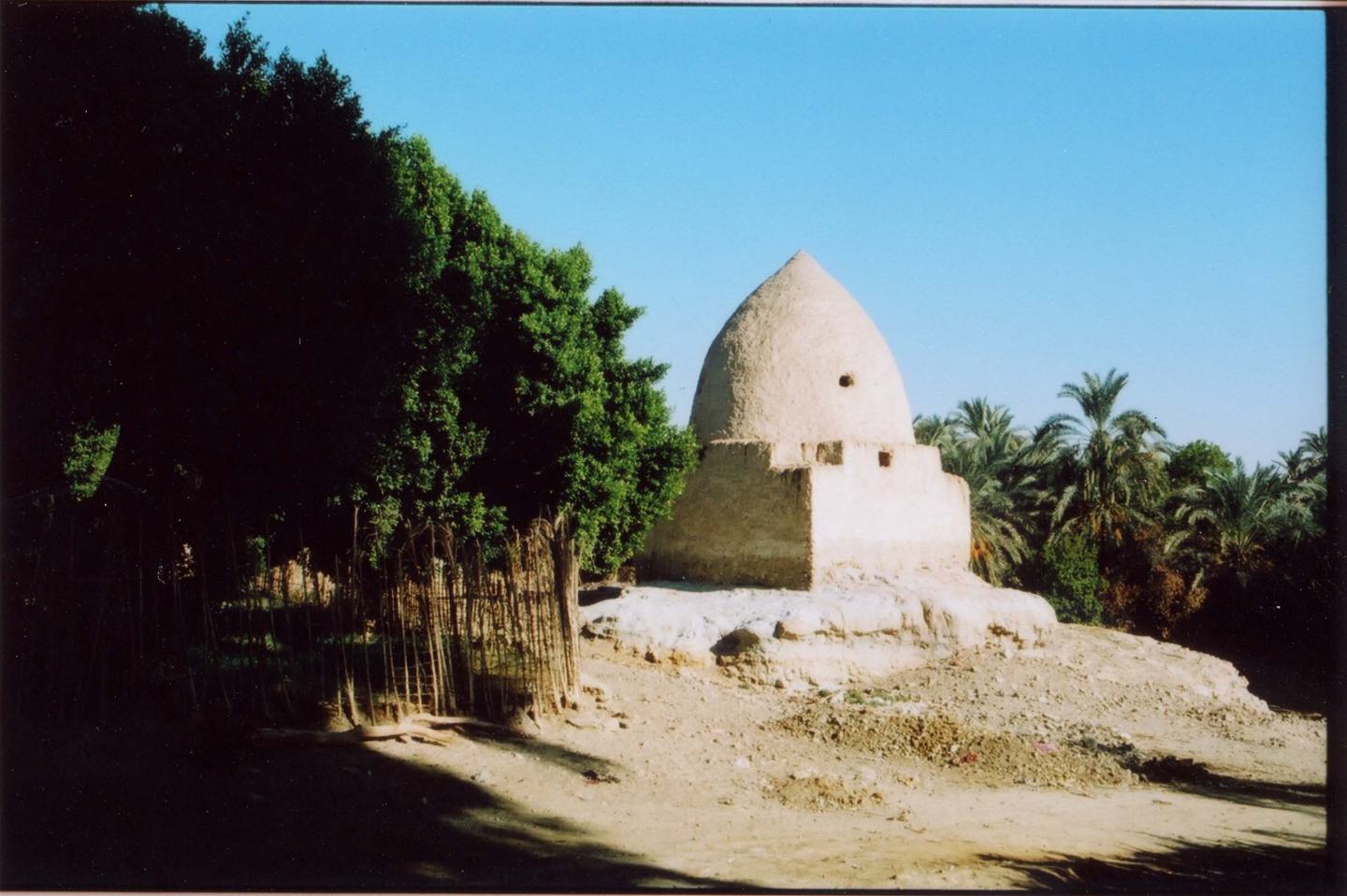

Over the last decade Carl Michael von Hausswolff and Thomas Nordanstad have been collaborating on a series of films documenting post-industrial locations, communities that once were seen as shining examples of man's development. Today these same sites appear as ghost towns, exploited and drained of their resources. The films shown at Oslo Kunstforening/Oslo Fine Art Society were made over a period of ten years at three different locations in Egypt, Japan and the US. Each of them tells a separate story but they also represent a continuum over the state of affairs. Al Qasr El-Wahat El-Bahriyah (the northern oasis) has been inhabited since the Neolithic period. The uninhabited island of Hashima outside of Nagasaki was populated for mining for a short period during the golden age of industrialism, while Electra in northern Texas still clings to the last drops of oil that the pump jacks are able to extract.

Carl Michael Hausswolff & Thomas Nordanstad, Hashima, Japan, 2002

The films are stretched out in time and lack plot, their musical undertones leaving an impression of dystopia. They all represent sites that more or less clash with the progress of man. Al Qasr, where water has always been the main source for growth, is perhaps the place that has been the least affected over the years. While Hashima stands as a symbol for the development that made Japan one of the world's leading economies, the island also represents the first stage of industrialization when coal was central to economic growth. Electra represents the second stage when the oil industry came to control large parts of the world economy and politics. Both locations carry an unmistakable imprint of the impact of human exploitation.

The three films can be seen in relation to what recently occurred in the Gulf of Mexico, Egypt and Fukushima. But they can also be looked upon as a contemporary Divine Comedy.(1) If Hashima represents Hell, Electra could stand as a metaphor for Limbo.(2) Al Qasr would then symbolize the Earthly Paradise, where you end up after being purified from sin and before entering the Heavenly Paradise.

Between 1887-1974 the island of Hashima filled to the breaking point miners and was emptied of its coal deposits below sea level. The barren island, exposed to typhoons most of the year, was counted as one of the most densely built places on earth.(3) In 1890, the Mitsubishi Corporation bought Hashima and in 1907 they completed the concrete wall that surrounds the island, which gave it its nickname Gunkanjima (battle ship island). In the 1910s the population had increased to over 3 000 and to provide housing the first concrete block in Japan was constructed. Each apartment consisted of a room of about 10 sqm. Baths, toilets and kitchen’s were communal. More blocks were built to meet the increasing production rates. In the 1940s, production had risen to over 400 000 tons, for which the miners, many of them prisoners of war from China and Korea, paid a high price. Numerous died, either in the mines or from undernourishment, or by throwing themselves into the sea, hoping to reach one of the neighboring islands. At the end of WWII about 1 300 men had perished. Population peaked in the late 1950s, with a density in the residential areas reaching 1 391 inhabitants/km².(4) In the 1960s when focus shifted from coal to oil the mining industry closed down around the country. Mitsubishi closed the Hashima pit in 1974. Since then the island has gone back to being uninhabited. The only thing indicating its recent history are the abandoned buildings, residential blocks, schools, hospitals and temples, all virtually in ruins. In 2009 part of the island opened to visitors after being kept closed for 35 years.

Carl Michael von Hausswolff & Thomas Nordanstad, Al Qasr Bahriyah Oasis, Egypt, 2005

Electra in northern Texas was founded in the 1850s by the Waggoner family for cattle farming. When the railway was built the investors were persuaded to place a station next to the ranch, which eventually expanded into the small town of Beaver Switch. In the early 1900s the town was renamed Electra after Daniel Waggoners daughter.(5) Due to the dry climate farmers often drilled for water, and in 1911 they hit oil. Soon the landscape was filled with the slow bowing of the oil pumps. The Waggoner ranch has many similarities with Reata in the movie Giant from 1956 with Elizabeth Taylor, Rock Hudson, James Dean. In the film we follow how oil transformed the Texas ranchers to the wealthiest in the country of their generation. The population of Electra grew rapidly and in the 1930s the town had 6 000 inhabitants. During the 1960s the population began to decline, and today it is estimated to less than 2 000. Since the early 2000s, Electra organizes an annual Pump Jack Festival.

Al Qasr is located in El-Wahat El-Bahriyah (the northern oasis), in a valley 360km southwest of Cairo. Agriculture has always been the main source of growth, mainly orchards, dates and olives, later mining and more recently tourism. The area consists of many small villages where el-Bawiti counts as administrative center; Al Qasr is located in its immediate vicinity. The population is of Wahati descent, which in Arabic means Those from the oasis, Bedouins who have inhabited el-Bahriyah since ancient times. The traditional song and music played on flute, drums and simsimeyya, is an important part of the culture of el-Bahriyah, as heard in the song of Hamed Alfrganeys in von Hausswolff’s and Nordanstad’s film. The city's austere appearance makes it perhaps difficult to distinguish any paradisiacal qualities at first sight, but there is something appealing in that so little has changed over the years, in that some processes are allowed to remain extremely slow, almost stagnant. When the paved road was built between Cairo and El-Bahriyah in the early 1970s, the isolation was broken. With the road came electricity, telephone and television. The Wahati dialect has since then also been affected by influences from Cairo. Today, tourism is an increasingly important source of revenue, primarily because of the graves that have been excavated lately. Al Qasr, Bahriyah is possibly the least dystopic of all three films, but towards the end you see a caravan of trucks filled with water from the oasis drive up the road in the direction of thirsty Cairo. Even in paradise, the outcome appears uncertain.

In Dante's universe Hell and the Heavenly Paradise are described as predetermined while Purgatory is depicted as an ascending spiral of transformation/progression were good and evil exists at the same time. The virtues are found side by side with the vices; confession, repentance and atonement. At the end you drink from the rivers Lethe (Good Remembrance) and Eunoë (Energy) before you finally reach the Earthly Paradise at the top of Mount Purgatory. It may seem paradoxical that the Heavenly Paradise, in contrast to the Earthly is described as static in nature. For is it not so that good and evil are reflected in each other, that the one can?t exist without the other? If we broaden our perspective and look down on Earth from above, we discover that everything exists simultaneously, night as well as day, present time as well as past and future (today, yesterday and tomorrow), winter, spring and summer, good as well as evil, love as well as hatred.(6) Perhaps it is in tension between these states that creativity is at its greatest, when you can sense fatal risks or imagine the state of an ecstasy we so rarely reach. What if it is as in the Talking Heads song, that Heaven is dead boring precisely because it is static; ”It's hard to imagine that nothing at all could be so exciting, could be this much fun. Heaven, heaven is a place, a place where nothing, nothing ever happens”. Or perhaps it is simply our physical nature standing in the way of Heavenly bliss.

About Carl Mickael von Hausswolff and Thomas Nordanstad

Since the late Seventies Carl Michael von Hausswolff has been working as a composer and as a conceptual artist focusing on photography, installations and performance. His works have been shown at biennials in Istanbul, Johannesburg, Manifesta in Rotterdam, Liverpool and Venice in 2001 and 2003, as well as at Documenta X in Kassel. During the 1990s Thomas Nordanstad ran galleries in Stockholm and New York organizing over 300 exhibitions with artists from Europe, the US and Asia. Since 1999 he has been working as a documentary filmmaker with productions such as Painting Pol Pot and Dictator’s Don’t Wear Jeans behind him. Carl Michael von Hausswolff was born in 1956. He lives and works in Stockholm. Thomas Nordanstad was born in 1964. He lives and works in Stockholm and Bangkok.

This is the first time within the Nordic countries that the films are presented together.

Footnotes

1. Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) allegorical poem is like all great art constantly up to date in that each reader is reflected in it. The Divine Comedy summarizes almost encyclopedic the figure gallery of classical literature, as well as figures from Dante's own time, while also depicting a religious and spiritual journey. Dante, The Devine Comedy, Part 1: Hell (1949), Part 2: Purgatory (1955), Part 3: Paradise (1962): Translated by Dorothy L. Sayers, Part 3 with Barbara Reynolds.

2. Limbo, from the Latin limbus for edge, referring to the border of Hell. In Limbo, the first circle of hell, one finds all those who have not been baptized and the so-called virtuous pagans. These innocent, yet cursed may spend life in a second-grade paradise. There are green meadows and a medieval castle with seven gates, which symbolize the seven virtues. You find pre-Christian figures such as Homer, Cicero, Caesar, Electra, Camilla, and Virgil, Dante's companion on the journey. Beyond the first circle, one finds all those who have sined by their own free will.

3. Hashima, The Ghost Island, Brian Burke-Gaffney, Cabinet, issue 7, 2002.

4. This figure is comparable to other densely populated areas in today's Japan, amounting to about 150 inhabitants/km². Today Monaco counts as the most densely populated country in terms of area with 16,688 inhabitants/km², the Vatican is next in line with 1,800, China 137, India 350, Norway has 14 inhabitants/km².

5. In The Divine Comedy Dante meets Electra in Limbo, she is the daughter of Agamemnon, who led the Greeks against the Trojans. According to Dante Electra is guilty of treason for having plotted the murder of her mother. She should have been placed in the ninth circle of Hell, but because the murder was in revenge of her father's death she was upgraded to Limbo. Whether Daniel Waggoner was aware of Electra's fate when he baptized his daughter and eventually named the city, we can not say.

6. When Dante reaches the eighth concentric sphere of Paradise he turns and looks back at the seven spheres he has already visited, and at earth placed in the center of the universe.

A conversation with Carl Michael von Hausswolff and Thomas Nordanstad will be held in conjunction with the opening.